Katja Phutaraksa Neef (she/they) is a political artist and activist

I first learned about the displacement of Banaban people in a Pacific Sociology course at university and was shocked and upset that I had previously never heard or learned about this history. As a colonial power, New Zealand exploited Pacific Islands including Banaba, part of modern-day Kiribati. From the early 1900s to the end of the 1970s, 90% of the island’s surface was mined by the British Phosphate Commission – jointly owned by the British, Australian, and New Zealand governments. This extractive practice created barren and uninhabitable land, resulting in the forced resettlement of Banaban people to Rabi Island in Fiji on December 15th, 1945. This displacement led to the loss of their Indigenous language and parts of their culture, genealogy, and ancestral lands.

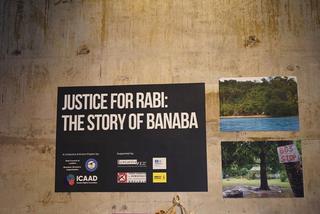

I became passionate about writing about this in my university assignments and applied to an artivism programme run by the International Center for Advocates Against Discrimination (ICAAD), who have a long-standing relationship on Rabi Island with the Banaban community. To my surprise, I was successful and decided to start a project on what happened to Banaba.

Fast forward two years and I have a close relationship with the Banaban Human Rights Defenders Network, have lived on the island for two months, and did my master’s research on youth activism on Rabi. Here are five things that I’ve learned along the way.

1. The power of solidarity: the importance of relationships

One of my biggest takeaways from working with communities as a human rights advocate is the importance of relationship-building and partnerships. Time and time again, I’ve found that the most valuable and impactful work comes from strong, organic relationships built with communities, people, and other advocates.

Earlier last year, we were able to bring over 13 youth advocates, dancers, knowledge holders, elders and community leaders to Aotearoa New Zealand. As part of an interactive exhibition, we showcased Banaban artwork, handicrafts, art-making practice, story-telling, and traditional dance to unpack and explore the history of Banaba and how it is deeply rooted in New Zealand’s colonial landscape.

The biggest impact was that the Banaban youth themselves were able to reclaim their history and stories and share them through different mediums. They could tell their own stories and narratives which impacted anyone they came across. The phrase ‘relationships are the project’ has always stuck with me, and I have seen the true meaning of it through the impactful and relational work that individuals can have.

In other situations, it is not safe for affected communities to speak out for themselves on the issues they face. As someone with easy access to public platforms and the safety to speak out against government bodies, I leverage my position to advocate for communities and to amplify their voices when in many cases they are unable to out of safety concerns.

2. Understand your power: play to your strengths and use your talents

Another key lesson I have learned as a young person is the importance of realising your own power and using your talents in any capacity in your advocacy work. This can apply to everyone. I have had a few young people talk to me about how they want to empower their communities or do human rights work but are studying engineering or doing a trade and think the only way to make an impact is to study a degree that aligns with this kind of work. My advice would be that if you are passionate and want to study, that is amazing! However, you do not need a background in human rights to be an incredible advocate.

Instead, you can have the most impact by using your skills and passion, whether it is public speaking, writing, or technical knowledge, to make a difference. This does not have to be your full-time career, unless you want it to be of course. Volunteering and doing advocacy work can be done by anyone in any field. Working towards transformational societal change can be within any space and field you pursue.

In my case, I have always enjoyed arts and photography, and I have used these skills in my advocacy. Art and storytelling are powerful ways to communicate and resonate with people. If you have talents such as dancing, singing, and painting, there are many creative and transformative ways to enact change.

3. There is not ‘one type’ of leader or campaigner that you need to fit

Something that I always struggled with at school and at university was worrying that I was not ‘cut out’ to be a leader or an advocate as I am not a confident speaker. Although I was extremely passionate, I believed people who were better at speaking than me would be better suited and that I shouldn't raise my hand. It took a while to realise that there are many different leadership qualities that are useful in different contexts, and there is not just one way to be a good advocate. As a leader, you do not have to be the loudest in the room but can create a space for others and pass the mic to voices that need to be heard.

4. Put yourself out there and find something you are passionate about

I think one of the hardest parts is putting yourself out there, especially with the fear of rejection. I learned that rejection should not prevent you from applying for or joining different clubs, initiatives, organizations, connecting with people, and reaching out. Although somewhat of a cliché, networking is the best way to build your connections and learn from others in the space. If you are passionate about an issue and want to create change, you can always research organisations in Aotearoa or overseas and get in touch. Cold emailing and reaching out might be intimidating, but organisations are looking for more young people to get involved in their work. Reaching out to someone a few years ahead on their advocacy journey or older can be a great way to learn more from their guidance, and most people would love a chat and a coffee!

5. You are never too ‘young’ or ‘inexperienced’ to get involved or create change

Whatever stage or age you are, it is never too late, and you are never too young to get involved in human rights advocacy. You do not have to be an expert or have all the skills - all you need is a willingness to learn and listen and a passion for the cause. I believe that actively listening is just as important as being a vocal advocate. Joining clubs, applying for internships, and learning about different issues are all steps you can take to be more exposed to what is happening and to find out how to be part of the change. Once you have found something you are passionate about, speaking to other young people or friends is a powerful form of advocacy.

Within every interaction, we carry our own forms of power and create power dynamics that we should always be aware of. Being aware of your positionality and being able to understand how it can impact the communities and people you engage with is crucial for a human rights advocate. Many groups face issues such as tokenism around the voices of Black, Indigenous, and people of colour, and there can be confronting conversations about Pākehā privilege and racism. Decolonization and cultural humility are not straightforward. Remember that human rights activism cannot be isolated from social and political issues and must be grounded within wider political and social philosophy centered around justice.

Finally, remember that change does not happen overnight: it takes commitment and time. In a world where we are all struggling with compassion fatigue, it is important not to lose hope.

Keep these points in mind when championing human rights:

- The importance of relationships. The most valuable and impactful work comes from strong, organic relationships built with communities, people, and other advocates.

- Play to your strengths and use your talents. Working towards transformational societal change can be within any space and field you pursue.

- There is not ‘one type’ of leader or campaigner. There are many different leadership qualities that are useful in different contexts.

- Put yourself out there. Networking is the best way to build your connections and learn from others in the space.

- You are never too ‘inexperienced’ to create change. Actively listening is just as important as being a vocal advocate.

About the Author

Katja Phutaraksa Neef is a political artist and activist born and raised in Thailand and grew up in Japan and Aotearoa. She is currently based in Tāmaki Makaurau.

Katja is currently an Artivist-in-Residence at ICAAD, and works at UnionAID as a programme coordinator for the Indonesia Young Leaders programme across East Indonesia and West Papua. Katja is also active in her community, having previously worked for Auckland Council as a Community Climate Catalyst and is a youth leader for the New Zealand National Commission for UNESCO. She has participated in field research and workshops in Fiji, Vanuatu, Thailand, Cambodia, Tanzania, Peru, Indonesia, and West Papua, with a regional focus on Asia and the Pacific. Her academic research and advocacy interests include issues concerning Indigenous rights, forced migration and displacement, and climate justice.